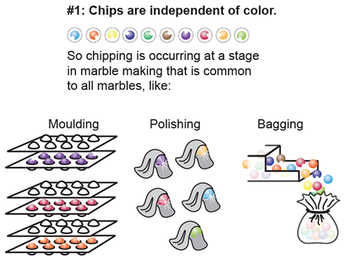

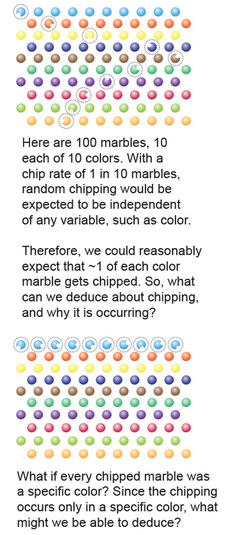

If chipping is random throughout all colors, what is statistically significant is the RATE of chipping, or number of marbles chipped per set of 100. If, however, only the blue marbles are chipped, that fact is also statistically significant, because now being blue seems related to being chipped. So, there could be two hypotheses drawn, depending on which scenario is found.

In scenario #1, we might then go on to look into what process in marble making might be responsible for chipping the marbles.

–For instance, could chipping be due to the molding process? Could it due to how quickly or slowly the marble mixture is cooled in the molds? Maybe the temperature difference between the marble mixture and the mold causes the marble to be more brittle, and thus more susceptible to chipping? Or maybe it happens as the top mold is clamped to the bottom mold?

–Could chipping be due to the polishing process? Is the arm that pinches and holds the marble chipping the marble, or is the arm agitated at too quickly such that polishing becomes abrasive? Is the buffing material too rough?

–Could the bagging process be chipping the marbles? Do the marbles tumble out too fast so as to bash against the shoot too harshly? Is the drop into the bag too great a distance?

In each of these processes, can you think of other investigations we'd need to do to follow up?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed