Every year, we the public hear about the new vaccine that will be produced to protect us from the upcoming flu season. The new vaccine designates the H’s and N’s that are being used in the coming year’s particular flu shot. What does this all mean, and why are these H’s and N’s so important?

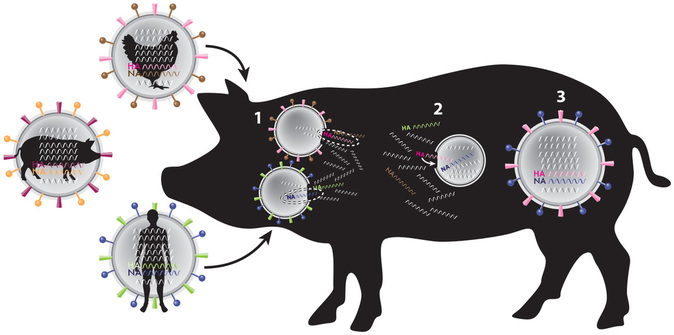

The H’s and N’s are quite important. They are the flu’s secret weapons, and the banes of our existence. Let’s look at the image. We noted that the flu can have different combinations of spikes on the outside of its capsule; they are the two structures our immune system uses to identify the virus as foreign invader. When a flu particle has a different combo of spikes, it’s classified as a strain, and is named for its H#N# accordingly. The number indicates how many spikes have been identified thus far: for the H there are 17 and for the N there are 9. These spikes are determined by 2 of the 8 gene segments the flu possesses. This point is also key to the flu’s success in evading our vaccines.

We also talked about how the flu can infect many species. In one species, like birds, the virus doesn’t cause problems, whereas in humans, it can cause sickness. The graphic shows this in an EXTREMELY simplified manner, where one variation of flu with pink and brown spikes can infect a chicken, while another with purple and green spikes infects humans, and a third strain with magenta and orange spikes infects pigs. Here’s the kicker: all three viruses can infect any of the species, so a pig can get a bird virus, a bird can get a human virus, etc.

It gets more complicated. Not only can one species get infected by two types of flu strains, but, that species can get infected AT THE SAME TIME with two different flu strains.

The pig, for example, can be affected by bird flu and human flu. So what, right? Well, let’s go back to the fact that a virus’ only agenda is to make more viruses. Once it finds a suitable host, like a pig, it will start taking over the cells, unpacking its gene segments, making multiple copies of all those segments, taking all the cell‘s resources to make new capsules and repack...the result being that multiple copies of new flu are made.

Now, what if two strains of the flu take over one cell? Do they fight until only one remains? NO. They both take over the cell. They both unpack their gene segments, make copies and repack. But the segments they re-pack may get mixed up; so long as there are 1 of each of 8 segments. Thus, within the confines of one cell, there are many segments flying about. And herein lies the danger, for new strains of virus can emerge, like this one with the pink and purple spikes in step 3. This phenomenon is called antigenic shift.

Next post, we’ll continue this story.

The H’s and N’s are quite important. They are the flu’s secret weapons, and the banes of our existence. Let’s look at the image. We noted that the flu can have different combinations of spikes on the outside of its capsule; they are the two structures our immune system uses to identify the virus as foreign invader. When a flu particle has a different combo of spikes, it’s classified as a strain, and is named for its H#N# accordingly. The number indicates how many spikes have been identified thus far: for the H there are 17 and for the N there are 9. These spikes are determined by 2 of the 8 gene segments the flu possesses. This point is also key to the flu’s success in evading our vaccines.

We also talked about how the flu can infect many species. In one species, like birds, the virus doesn’t cause problems, whereas in humans, it can cause sickness. The graphic shows this in an EXTREMELY simplified manner, where one variation of flu with pink and brown spikes can infect a chicken, while another with purple and green spikes infects humans, and a third strain with magenta and orange spikes infects pigs. Here’s the kicker: all three viruses can infect any of the species, so a pig can get a bird virus, a bird can get a human virus, etc.

It gets more complicated. Not only can one species get infected by two types of flu strains, but, that species can get infected AT THE SAME TIME with two different flu strains.

The pig, for example, can be affected by bird flu and human flu. So what, right? Well, let’s go back to the fact that a virus’ only agenda is to make more viruses. Once it finds a suitable host, like a pig, it will start taking over the cells, unpacking its gene segments, making multiple copies of all those segments, taking all the cell‘s resources to make new capsules and repack...the result being that multiple copies of new flu are made.

Now, what if two strains of the flu take over one cell? Do they fight until only one remains? NO. They both take over the cell. They both unpack their gene segments, make copies and repack. But the segments they re-pack may get mixed up; so long as there are 1 of each of 8 segments. Thus, within the confines of one cell, there are many segments flying about. And herein lies the danger, for new strains of virus can emerge, like this one with the pink and purple spikes in step 3. This phenomenon is called antigenic shift.

Next post, we’ll continue this story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed